Introduction

Earth science provides a lens to explore the planet’s climate history, revealing how natural processes have driven changes over millions of years. Geological records, from the Phanerozoic Eon to the Holocene Epoch, show a dynamic Earth shaped by cycles of warming, cooling, and environmental shifts. By examining these periods, we can understand the interplay of CO2 levels, continental drift, and random events like meteor strikes. This page delves into Earth’s climate past, focusing on key geological periods, natural processes, and historical shifts, using data to highlight the planet’s complex climate system and the insights Earth science offers into its long history (see also Holocene Climate).

Key Terms

MYA: Million years ago, a unit of geological time (Stanley, 2009).

PPM: Parts per million, a measure of CO2 concentration in the atmosphere (Stanley, 2009).

Actualism: The principle that past geological processes are similar to those today (Stanley, 2009).

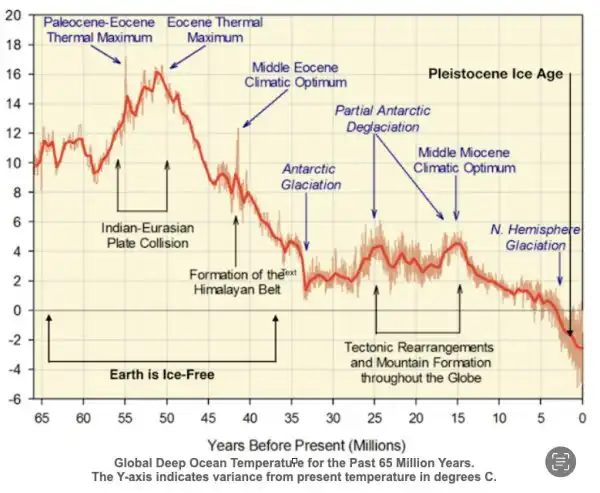

Global deep ocean temperatures over the past 65 million years.

Geological Time Framework

Earth’s climate history spans vast geological periods. The Phanerozoic Eon, beginning 542 MYA, saw the rise of complex life and includes the Cenozoic Era (65.5 MYA to present), often called the Age of Mammals, marked by mountain building and a cooling trend over the last 34 million years (Stanley, 2009). Within the Cenozoic, the Neogene Period (23 MYA to present) experienced continued cooling, shaping modern climates. The Holocene Epoch, starting 11,700 years ago, brought significant changes, such as the flooding of the Chesapeake Bay as glaciers melted after the last Ice Age (Stanley, 2009). These periods provide a framework for understanding climate shifts, showing how Earth transitioned from warmer, wetter conditions with higher CO2 to cooler, drier climates driven by natural processes like glaciation and ocean currents.

Natural Processes in Climate

Earth science relies on actualism—the idea that geological processes like erosion and volcanism operate consistently over time (Stanley, 2009). A key process is CO2 regulation: warmer temperatures increase evaporation, leading to more rain, which dissolves CO2 into a weak acid. This acid, along with decaying plants, erodes rocks, releasing calcium and magnesium that form carbonate rocks (e.g., limestone) in oceans, locking away CO2 (Stanley, 2009). Continental drift also shapes climate; 34 MYA, Antarctica’s isolation created a circumpolar current, cooling the planet by reducing heat transfer (Stanley, 2009). Homeostasis and hysteresis add complexity—deep oceans, still warming from the Little Ice Age (ended ~1850 CE), show delayed responses to surface temperature changes, illustrating how natural systems resist and lag behind climate shifts (Stanley, 2009).

Historical Climate Shifts

Geological records reveal dramatic climate shifts. During the Eocene Epoch (56–34 MYA), CO2 levels reached 2000 PPM—10 times today’s levels—due to high volcanic activity and water vapor, creating a warm, wet Earth with global temperatures ~12°C higher than now (Stanley, 2009). The Miocene (23–5.3 MYA) saw cooling, with CO2 rising from 200 to 320 PPM as forests declined by 50%, giving way to grasslands (Stanley, 2009). The Pliocene (5.3–1.8 MYA) began warm—England was subtropical with temperatures 3–4°C above present—but ice ages started by 3.2 MYA, freezing the Arctic by 2.6 MYA (Stanley, 2009). In the Holocene (11,700 years ago to present), hyper-warming 9,000–6,000 years ago raised temperatures by 1–2°C, enabling agriculture in Europe, though sudden sea level rises ~7,600 years ago killed Caribbean corals (Stanley, 2009).

Random Events and Climate

Unpredictable events have significantly influenced Earth’s climate. Meteor strikes, like the 66 MYA impact that ended the dinosaurs, released dust and gases, cooling the planet by blocking sunlight for years, with global temperatures dropping ~5°C (Stanley, 2009). Cosmic rays—high-energy particles from space—can affect cloud formation, potentially cooling the Earth, though their impact varies (Svensmark, 2012). Solar output also fluctuates; the Medieval Warm Period (900–1300 CE) saw increased solar activity, raising European temperatures by ~1°C, supporting Viking settlements in Greenland, while the Little Ice Age (1300–1850 CE) experienced lower solar output, cooling the region by 0.5–1°C and expanding glaciers (Stanley, 2009). These events highlight the role of natural variability in climate history, often driving rapid, unforeseen changes.

Holocene temperatures versus CO2 do not track each other suggesting other factors at play.

Earth’s Cyclical Nature

Earth’s climate operates in cycles, with periods of stability interrupted by rapid shifts. In the Holocene, the Northwest Passage opened three times due to sea ice melt, as shown by whale bone fossils, reflecting natural warming phases (Stanley, 2009). Hyper-warming 9,000–6,000 years ago allowed agriculture to spread across Europe, while the Medieval Warm Period supported Viking settlements, followed by the cooling Little Ice Age, which led to their abandonment by 1400 CE (Stanley, 2009). Over the Cenozoic, cooling trends were punctuated by warm intervals, driven by CO2, water vapor, and continental movements (Stanley, 2009). These cycles demonstrate that Earth’s climate is dynamic, shaped by natural processes like glaciation, ocean currents, and solar variability, often independent of predictable patterns.

Conclusion

Earth science illuminates a climate history defined by natural cycles and unpredictable events, from the Eocene’s warmth with 2000 PPM CO2 to the Miocene’s cooling and the Holocene’s rapid shifts (Stanley, 2009). Processes like CO2 regulation through rock weathering, continental drift, and random events like meteor strikes reveal the planet’s complex climate system. Historical shifts—such as the Pliocene’s ice age onset or the Medieval Warm Period—underscore the Earth’s cyclical nature, driven by natural forces over millions of years. Studying these patterns through a data-driven lens provides critical insights into Earth’s past, emphasizing the importance of geological records in understanding its climate history.

References

- Stanley, S. M. (2009). Earth System History.

- Svensmark, H. (2012). Cosmic Rays and Climate. Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics.

- Infiltration by Progressive ideology:

- Resources: Challenging Elite Narratives (Read first.)

- Socialism and Communism: Unmasking the Shared Ideology - BristolBlog.com

- The Progressive Bias in Science: Why Trust Is Eroding - BristolBlog.com

- Peer Review Problems: Is Science Truly Objective? - BristolBlog.com

- Climate Change Funding: A Science-Industrial Complex? - BristolBlog.com

- NASA’s Climate Science: Ideology Over Evidence? - BristolBlog.com

- Environmentalism’s Anti-Human Bias: A Threat to Progress - BristolBlog.com

- Models Overhype Sea Level Rise - BristolBlog.com

- Global Grain Surge Challenges Climate Predictions: 2025 Update - BristolBlog.com

- Tibet Tree Rings Reveal Natural Climate Cycles - BristolBlog.com

- Climate Models Miss the Mark: U.S. Thrives Despite Alarmism - BristolBlog.com

- Are Climate Policies About the Environment or Money? - Bristol Blog

- Earth Science Insights: Historical Climate Change Over Geological Time | Bristol Blog

- How CO2 and Climate Shape Plants: C3, C4, and Greening - Bristol Blog

- Tuvalu Atolls Debunk Sea Level Hype - BristolBlog.com

- Other:

- Unmasking Fake News: How Media Fuels Violence and Immigration Fear

- Black-on-Black Crime Ignored by Press: Chicago’s Slaughterhouse | Bristolblog

- Crime Surge and Pub Closures: London’s Multicultural Collapse | Bristolblog

- Middle East Chaos: Overpopulation and Religious Violence, Not Climate | Bristolblog

- Islam vs. West: Press Bias Fuels Muslim Violence and Silences Reformers | Bristolblog

- Democrat Identity Politics Fuels Muslim Religious Violence | Bristolblog

- Turkish Alevism: A Distinct Faith, Not Islam | Bristolblog

- Immigration Challenges in East Tennessee: A 2025 Update - BristolBlog.com

- Marijuana’s Risks: Addiction, Mental Health, and Crime in Bristol, Virginia - 2025 Update

Media bias and closed discussions: